According to Wall Street, the recession should've already been here by now. Meanwhile, permabull Tom Lee's been right all along—is this the most hated bull market in history?

Tom Lee of Fundstrat has gained a reputation of being one of Wall Street's biggest optimists. He's so optimistic about the market—and seemingly almost all of the time—many have labeled him as a perma-bull.

But if you listen to Tom, he's clearly no fool. He supports his case with statistics and a thoroughly researched macro-economic view. And while he's not always right (as 2022 clearly didn't turn out to his favor), he's certainly winning the day for 2023.

Back in January, Fundstrat's Tom Lee at the beginning of the year made the following predictions:

- The S&P 500 would rally 20% in 2023.

- Inflation would cool and the Fed would pause.

- His end of year S&P 500 target is 4,825.

And so far...he's looking to be dead right as the S&P 500 grinds up towards 4,600.

So while the majority of both Wall Street and Main Street sit on the sidelines, and Tom Lee continues to be right, we have to ask:

Is this the least expected, most hated bull market in history?

Bull Case: Scared Money Don't Make Money

The consensus on Wall Street has been that the U.S. is expected to fall into a recession in 2023 due to the Fed's fight against inflation, and that the indicators the Fed has been looking for include slowing job creation, slowed wage growth, and rising unemployment—all pointers to a recession.

However, the consensus has been expecting that recession to arrive as far back as March—the recession should already be here. So where is it?

According to the consensus on Wall Street, the recession should already be here—so where is it?

The bull case that Tom Lee and other bulls are advocating is that according to all current indicators, the economy is not sliding into a recession but sliding into an expansion.

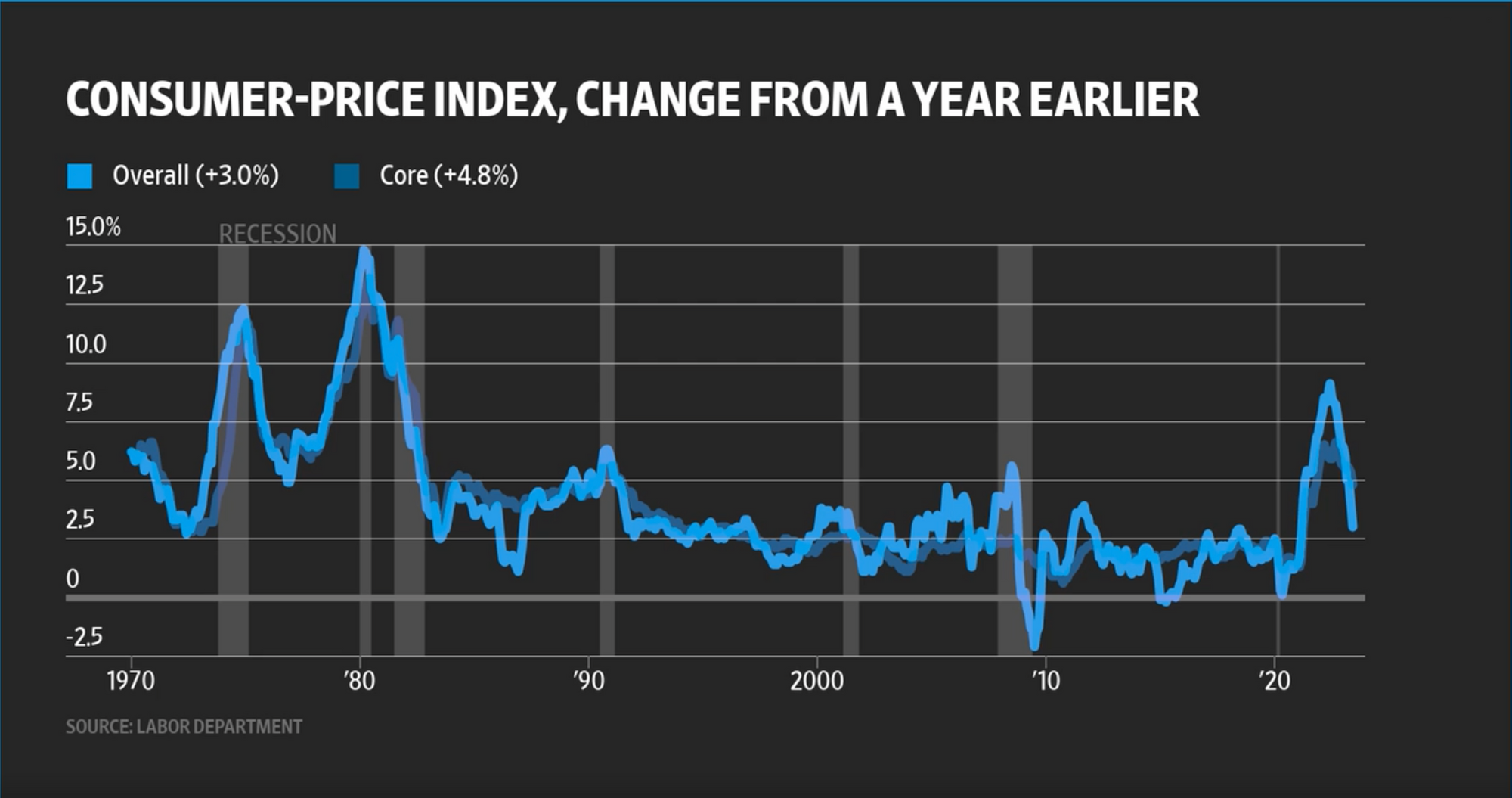

Nowhere is that more apparent than in June's CPI reading, as Core CPI has fallen to 3.0% in June:

Lee's macro-view is that the Fed is not trying to kill the economy—they're trying to kill inflation and they're clearly winning, which means after one more potential hike in July, pauses will soon be followed by rate cuts.

In other words, Lee's Bull case is based on the fact that a clearing through the forrest is appearing without the Fed having to burn all the trees down.

His case is also based on the fact that things have been really pushing inflation—things like used car prices, housing, and wages—have nothing to do with the stock market.

Remember in rally after Covid in 2020 and that familiar adage?

"The stock market is not the economy."

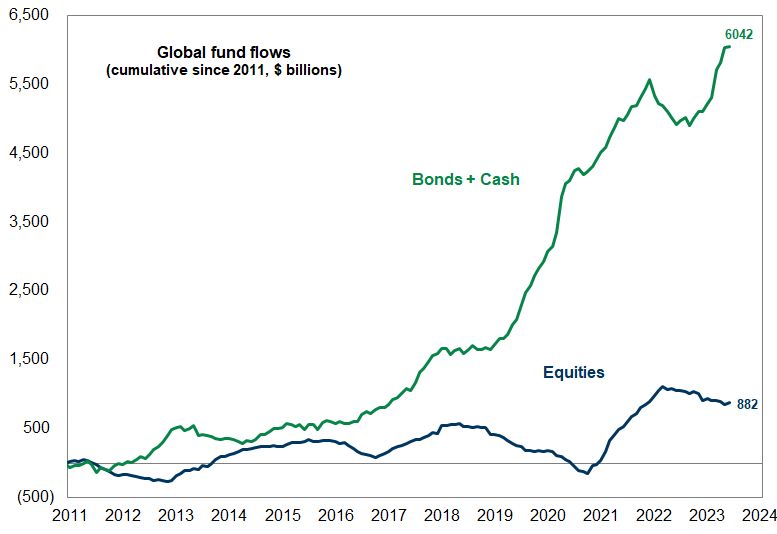

And with cumulative majority global fund flows remaining in bonds and cash, there is a very clear wall of capital waiting for the all-clear to dive back into equities, much more so than is already currently in the market.

Lee's viewpoint is that the market has potential to rally another 8-12% by the end of the year, bringing the S&P 500 to between about 4850 and 5000.

This rally will be lead by the cyclical sectors, with FAANG/Tech leading the charge. He's also expecting Industrials to lift and Energy will also catch a bid.

What About The Inverted Yield Curve?

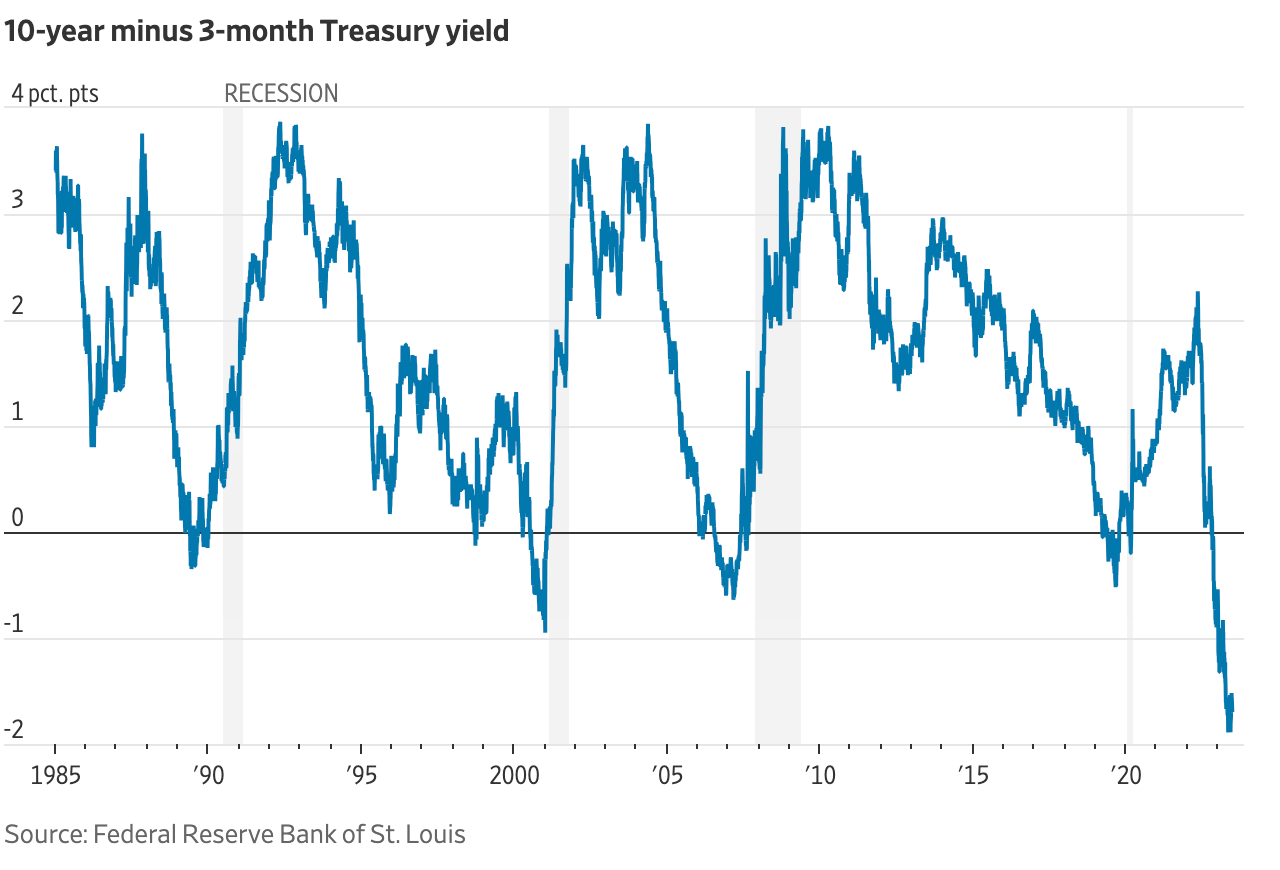

Campbell Harvey, a professor at Duke University, points out that investors and economists learned a hard lesson in 2008-2009, as many had dismissed the earlier yield-curve warning.

The inversion could cause a recession in two ways.

First, it could become a self-fulfilling prophecy, as investors and CEOs see the inverted yield curve as a signal to cut back risk-taking in expectation of a recession, creating the very economic weakness they were worrying about.

Second, an inverted curve hurts the basic business model of banks, that of borrowing short-term and lending long-term, hitting profits and reducing lending—again, bad news for growth.

But if that's true—why did J.P. Morgan's total profits just soar 67% on earnings, even after swallowing First Republic?

The largest consumer bank reported earnings last week—revenue increased 37%. and profit soared 67% to $5.31 billion, lifted by rising interest rates since the bank was able to charge more on loans.

Which begs the question...

Shouldn't the inverted yield curve be undermining J.P. Morgan's net interest income?

The truth of the matter is that JPMorgan Chase & Co and other large banks fund more than half of its balance sheet with low-cost deposits.

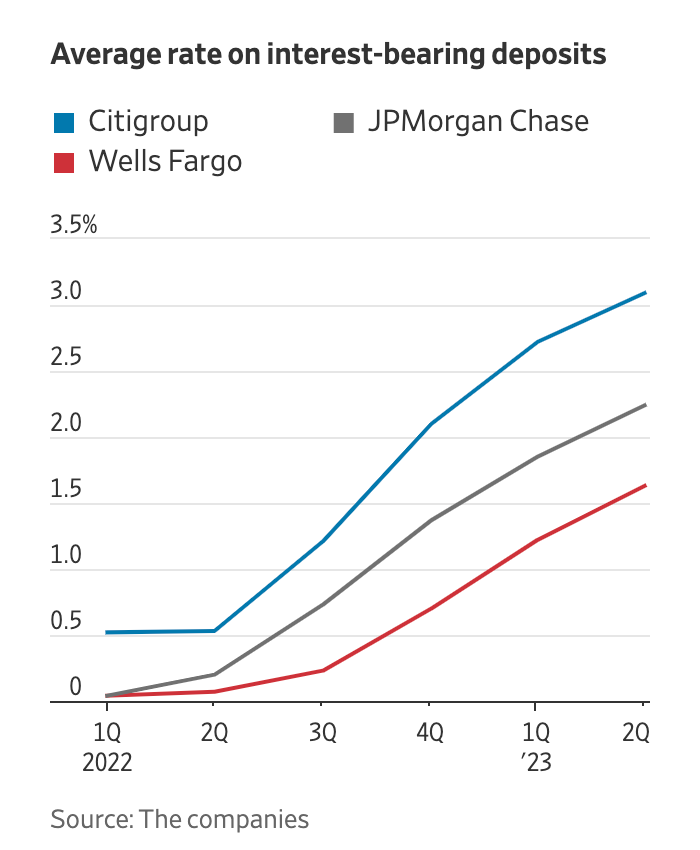

The average rate for all of JPMorgan's interest-bearing liabilities is only 2.24%—that is a long way from today's 4.61% yield on 2-year Treasuries.

Also, many commercial and industrial loans are floating-rate term loans, or revolving loan facilities with floating rates tied to short-term benchmarks, which have increased sharply this year in anticipation of Fed rate hikes.

In the U.S., rates usually come down because there’s a recession—but not always.

In 1966 the curve inverted without signaling recession, although each of the next eight recessions was preceded by an inversion, with no more false signals.

The yield-curve record in other major countries is much worse, with the U.K. inverting six times with only three recessions since the 1980s—and it is inverted again now.

So is the inverted curve a 100% perfect predictor of recessions as common financial lore says it is? Hardly.

It's hard to argue that the 2019 inversion predicted the pandemic, or that the 1973 inversion predicted the Arab oil embargo. In both cases, those keen on the yield-curve signal would have to argue that even without the surprise shocks, there would have been a recession.

Equally, the U.S. “recession” of 2001 never had the two successive quarters of falling gross domestic product—the definition of a recession in most countries.

A Recession May Not Matter For Stocks

Again going back to the 2020 narrative where the stock market is not the economy, this begs the question...

Does a recession even matter for stocks?

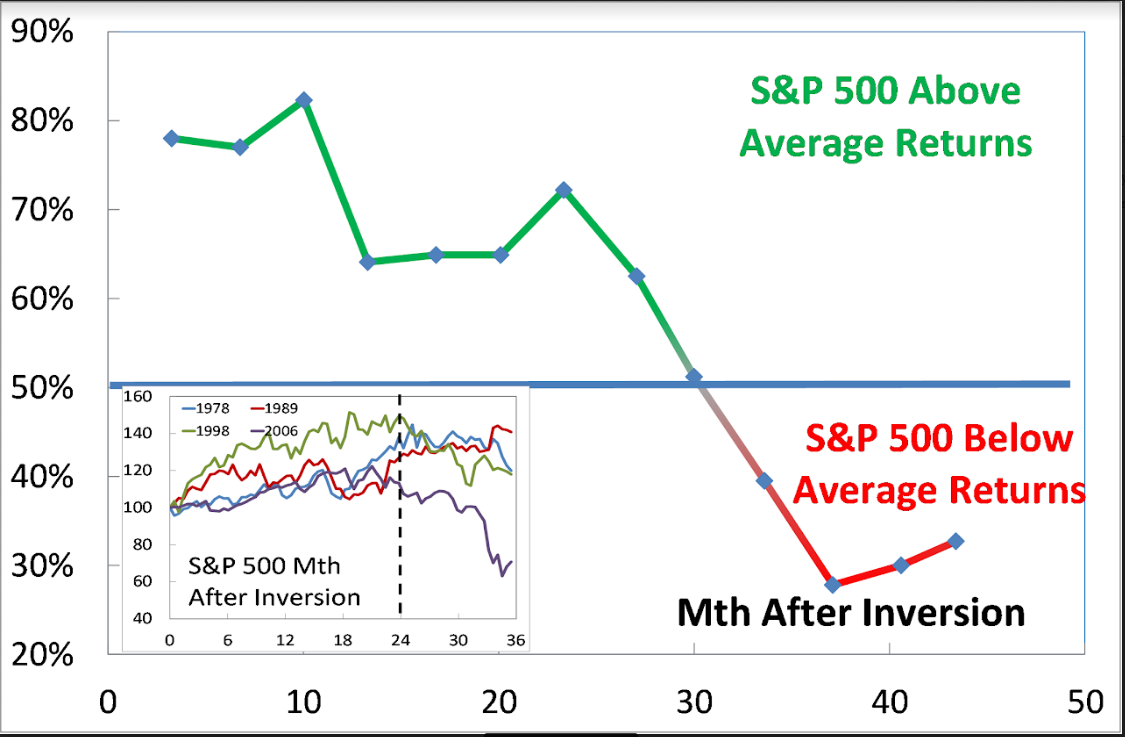

Apparently it doesn't, according to J.P. Morgan's top quant Marko Kolanovic. Historically, S&P 500 returns remain above average for 30 months after a yield curve inversion.

“Historically, equity markets tended to produce some of the strongest returns in the months and quarters following an inversion. Only after [around] 30 months does the S&P 500 return drop below average,” said Marko Kolanovic.

So if the yield curve inverted in March of 2022, 30 months later puts us out to September 2024—just in time for the presidential election and the October Surprise—coincidence?

What About The Banking Crisis?

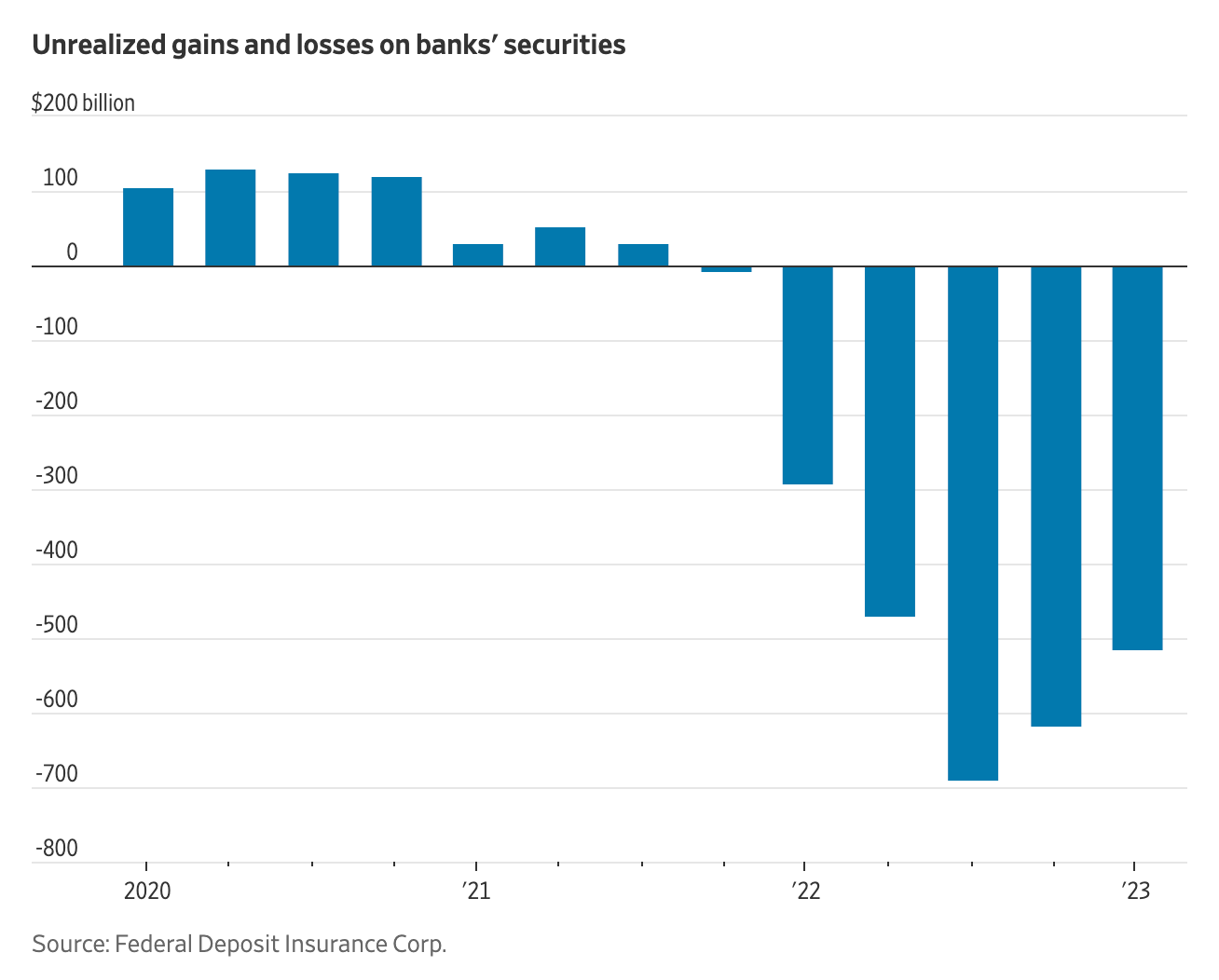

The major banks killed earnings last week and we're getting our first glimpses into regional banks reporting this week. But from what we can see, the unrealized losses on bank securities has actually been improving since October 2022.

So while there's still risk for that systematic risk to reverse direction as commercial real estate continues to deteriorate, banks like Wells Fargo have been preparing for this, socking away $1B more in reserves to prepare for any adverse mark-to-market results.

Is This The Bull Market?

Looking purely at the evidence and all current economic indicators, it would appear so. With the VIX and market volatility at an all time low, there's little standing in the way of the market continuing to grind upwards.

And while the bearish consensus remain cautious and on the sidelines, the old adage of Wall Street seems to be playing out—the consensus rarely makes money—they're late to react and follow the herd to be safe.

In other words—scared money don't make money.

Could something happen in 2024 as we enter an election year? Perhaps, and by then maybe the yield curve will be more in its predictive phase.

But for 2023, it seems there's little in the way of this bull market.

Register For Free in Seconds! Click The Image

Did you enjoy this analysis? It was super easy to do using a free account on Synvestable, the absolute best app in finance.

Register in 3 seconds using your Google Account!